Eli Noer Fadilah, The Lives of Strangers, 2025. Sing Lit Station.

III. A new political subject: The peak of migrant poetry (2018-2021)

Written by Ada Cheong

Dated 18 Dec 2025

2018 – Call and Response, a local/migrant poetry collaboration

2018 – Familiar Strangers, anthology of poems and short stories by Indonesian MWs

2018 – Stranger to Myself, award-winning collection by Md Sharif Uddin

2019 – Dreams are My Reality, poetry and short story collection by Shy Lhen Esposo

2019 – I dream of Singapore, documentary film about MWs in

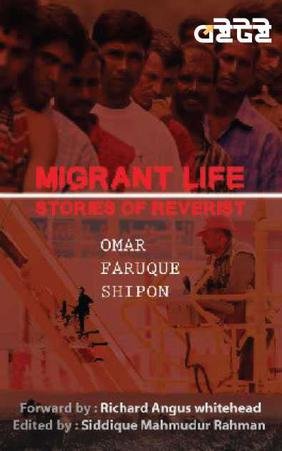

2020 – Migrant lives, poetry and short story collection by Omar Faruque Shipon

2020 – No Cinderella?, poetry collection by Rolinda Onates Española

2020 – “First Draft” by Zakir Hossain Khokan published online

2020 – Translating migration, an international migrant poetry collection

2021 – Call and Response 2, a local/migrant poetry collaboration

2021 – Stranger to my World, poetry and diary entry collection by Md Sharif Uddin

2021 – “Please do not call us your brothers” by Zakir published on Facebook

Following the post-riot surge in migrant literary activity between 2014-2017, poets began to assume greater agency over the production and circulation of their own work. As Ibrahim points out, MWPC “opened doors” for migrant poets in Singapore. In the years leading up to and during Covid-19, these writers emerged not only as literary voices but as political subjects. For many, writing and dreaming are inseparable acts. Through the potent act of writing, migrant poets create new roles and possibilities for the migrant precariat, transforming themselves from alienated, liminal figures into active community organisers who create spaces for empathy and activism.

Enabled by the success of MWPC, the wider migrant arts scene also saw a flush of activity in this period as local circles increasingly rallied behind migrant writers and artists. There was a proliferation of migrant arts events from 2018 onwards, including the Migrant Cultural Show (est. 2018), Global Migrant Festival (est. 2018), Migrant Literature Festival (est. 2019), and Migrant Heroes Festival (est. 2019). Furthermore, migrant workers were included in and supported by other local arts spaces: The Necessary Stage supported the creation of Birds Migrant Theatre in 2018, and Bangladeshi poets Razib and Tabangura were invited to contribute to Substation Theatre’s alieNATION project (2020). Migrant writers and artists begin to take the lead in organising such cultural activities, with key figures including: Zakir Hossain Khokan, Md Sharif Uddin, Rolinda Onates Española, Bhing Navato, Ripon Chowdhury, AK Zilani, and Fazley Elahi Rubel.

The swell of migrant poetry in this period makes it impossible to examine every text in detail here. In what follows, I focus my analysis around three clusters of texts: (1) the Call and Response anthologies; (2) collections by Shy Lhen Esposo, Rolinda Onates Española, and Omar Faruque Shipon; and (3) Zakir’s and Sharif’s Covid writings.

The Call and Response anthologies

The two Call and Response (C&R) anthologies were published by Math Paper Press in 2018 and 2021 respectively, to showcase migrant and local poetry alongside each other.

In these anthologies, a deeply collaborative creative process emerges, marking a shift from earlier collections where migrant poets wrote, then had their works translated (often with the help of a local writer or editor) for the consumption of local audiences. C&R1 was edited by a team of local and migrant poets that consisted of Rolinda Onates Española, Zakir Hossain Khokan, and Joshua Ip. Rolinda and Zakir assumed leading roles in the editorial process, curating and managing the translations of migrant poems for the collection. As Ip describes in the Foreword, it was “two migrant writers charging ahead calling out "HURRY UP ALREADY”, and one flustered Singaporean running behind them” (xv). C&R2 was likewise organised and curated by a team of local and migrant poets: Bhing Navato, Zakir Hossain Khokan, Joshua Ip, and Poh Yong Han. Across the two collections, the process of translation is never really detailed; there is little information about what language the original poems were submitted in, nor who translated them into English. The poetic conversation is largely conducted and presented in English.

The anthologies invite a critical evaluation of migrant poetry itself, not only as a body of work to be celebrated and recognised as literature worth reading, but also as a term that is fraught with discontents. As Poh points out in the Afterword to C&R2, the labels migrant and worker both risk reproducing the expectations that Singaporeans map onto them, “unconsciously promot[ing] reductive tropes of migrant suffering or oppression, and further reinforcing their othering” (299). The alien/citizen distinction can be extremely uncomfortable and unhelpful, especially given its “arbitrariness” (Ip C&R2, “Foreword); Singapore itself is a nation of migrants, and migration is a widely-shared experience.

Yet, to toss out these labels in the name of inclusivity can feel disingenuous. There is a certain discomfort in disengaging from the precarity faced by migrant workers and flattening out the experiences of migration, that emerges for example in Janice Heng’s “#EquatorialWhiteCollarProblems”, Zhang Ruihe’s “Mid-April in Pittsburgh”, or Yong Shu Hoong’s “One Rainy Afternoon in Oxford”. This is not an accusation of individual writers being tone-deaf, or an attempt to hold them at fault; they write beautifully, and through their words, they articulate the undeniable universality of alienation and longing in migration. But the desire to erase the local/migrant binary and its prejudices raises certain challenges. Can—and should—we talk about migration without serious engagement with the inequalities that structure the world-system? As Poh writes, “the voice-giving ability of migrant writing is constrained by the specific political realities in which it is situated” (C&R2, 297). To dislike using the local/migrant distinction, then, is to dislike the policies that systematise the vulnerability and transience of migrant workers.

Yet, the C&R anthologies enact a vision of a shared literary space that challenges and strains to reach beyond the systemic inequalities that shape Singapore. In doing so, they exemplify a politics of inclusion that can be understood as a form of dreamwork. In C&R1, poetic creation becomes a form of empathetic listening; at its best, it goes beyond the simplistic act of ‘putting yourself in another’s shoes’, achieving moments of recognition and empathy through linguistic transformation and echoing. In C&R2, the migrant poetic voice truly comes into its own; and in dialogue with their paired writing partners, the poems exhibit a greater degree of irrealism, experimentation, and play. Read together, the two anthologies confront the strangeness of Singapore’s neoliberal capitalist realism, and dream of a future in which the inequalities between migrant / local can truly be dissolved.

“Call and Response” is a fitting description of the process of creating the first anthology. Led by Zakir and Rolinda, migrant poets had their works written and translated first, forming the call to which local poets, organised by Joshua Ip, responded to. Each migrant/local pair is featured on adjacent pages in the anthology, and the migrant voice is heard, echoed, and transposed within the local writer’s poem. If the dreamwork of the early waves of migrant poetry was to make the city strange, empathy itself becomes the dreamwork that unfolds in C&R1. The resulting poems do not resolve or explain the structural inequalities around labour and migration, but allow its emotional charge to reappear, refracted and reconfigured in unexpected ways.What emerges is the nuanced practice of empathetic listening, an imaginative labour that reaches for a world where the precarity and inequality faced by the migrant precariat is history.

In the most powerful pairings, images from the migrant writer’s pen are arrested, illuminated, and refracted. For example, the long journey of chasing the migrant dream in Shobina Suja (Rose)’s “The Yellow Bird” is witnessed and inflected in Teo Xiao Ting’s “The Feather Lights”. Rose’s poem takes the form of two quartrains and a third stanza of 9 irregular lines. In the quartrains, the phrase “If only I could” is repeated in the first two lines, signalling a desire, a reaching towards a better place and time. This reaching finds its release when the second stanza culminates in an image of a familiar home that brings peace and warmth:

If only I could return to the lit terrace in the winter-dusk,

I would have wrapped my body in that old shawl

and watch how the sun sets in the west.

In the third stanza, however, this idyllic image of dusk dissolves as the speaker recalls the present, beginning with a single word: “Now”. Her longing is replaced by a more sobering reflection on her present, caught between a past (“afternoons spent in song”) and the future (“darkness arriving with the night”). Rather than a bird that “could touch the horizon”, she feels like a “boat (that) has sailed so far / on this curved journey”. Oscillating between the soaring hope and interminable drudgery of the migrant journey, the speaker has only grim resolve to hold on to.

The simultaneous longing and lethargy of the migrant journey, rendered in Rose’s poem through the slow curvature of a sailing boat, finds its echo and transformation in Teo’s response. Both poems share an identical stanzaic structure, yet Teo’s refraction of Rose’s imagery alters its emotional current, forming a clear-sighted recognition of both the pain and strength it takes to hold onto hope. While Rose’s poem ends with the boat, the liquidity of its long glide seeps into the earlier stanzas of Teo’s, and other images it reproduces become wet: the road becomes a “concrete floor floods haphazard”, and the setting sun becomes one that “drips, dips a gliding departure”. In Teo’s response, the migrant’s endurance takes on a quietly luminous force. The woman who once merely watched the sunset is illuminated from within, now reimagined as one who can “wrap a cotton embrace threadbare / around a miniature sun, [her] heart.” Hope is not a distant destination, but something that “arrives / as a feather”, “a conversation whispered into a fist”. In this way, the titles of the poems also converse; Teo’s poems lights the feathers of the yellow bird in Rose’s. It witnesses the difficulties of doing so, while rooting for the “dream wing” of this bird.

Likewise, both Mohiuddin’s “Windfall Dream” and Theophilus Kwek’s “The Way Light Works” speak to each other through the shared motif of light. In open couplets, Mohiuddin’s speaker dreams tenderly of a loved one, her hair forming a “bed of clouds” softly lit by “the circle of stars” and “hairs embroidered with fireflies”. Kwek’s poem begins where that dream ends: at dawn, when the migrant must return to the stark reality of labour. Beginning with sunrise, where the sun is “still the colour of cheap vests”, the speaker witnesses how it “turns white an O like a speed-sign” and then becomes like “the moon when they show it in pictures”. The sun’s glow, now flattened and bleached, exposes everything under an unbearable light. Formally, Kwek reflects this disorientation: the speaker has more questions than answers, the absence of punctuation causes each thought to bleed into the next without a clear connection, and the poem’s justified lines stretch to both margins, making the length of each line indistinguishable from the next. Kwek’s poem is an empathetic response to Mohiuddin’s, contrasting its luminosity with the glare of the everyday to acknowledge the exhaustion and fragility behind Mohiuddin’s dreamscape.

The empathetic dialogue initiated in C&R1 transforms, in C&R2, into an irrealist poetics that not only subverts the eeriness of Singapore’s neoliberal realism, but laughs at, and dreams beyond it. In the second anthology, the poetic conversation becomes more daring, with a greater degree of irrealism, experimentalism, and play. As Singapore was brought to a halt during Covid-19, C&R2 brought together seventy-two poets, local and migrant, who collaborated over email and WhatsApp to craft their paired poems. Rather than simply being heard or represented, migrant poets now shape the shared dreamscape of Singapore itself with their local counterparts.

In C&R2, migrant writers explore perspectives other than their own, writing from a greater variety of perspectives than that of the domestic or construction worker. In “Unwanted”, Yulia Endang writes from the perspective of the male cleaner in Dave Chua’s “Shoes”. Rolinda Española also writes the perspective of a Filipino seaman, another figure of precarious transnational labour. This dip into fiction suggests a growing confidence and elasticity in the migrant poetic voice: no longer confined to documenting their own suffering, these poets articulate a certain solidarity with other precarious migrant labourers.

Refusing poverty-porn expectations, pairs of writers stretch reality to its limits, defamiliarising the migrant experience through irrealist and magic realist strategies. Bodies are transfigured (like the broken man in V Khan’s poem with floating eyes and eyes in his heart), and chimeric beings (such as the tiny migrant sparrows and Singaporean flamingos who complain hilariously about frozen algae in Gemma P. Duldulao and Yolanda Yu’s poetic pairing) become a means of registering the precarity of migrant life. Gone is the eerie, gothic city of Sharif’s and Mukul’s poetry; it is instead transformed into something more whimsical and mythical in C&R2. Rather than a city where “Workers wash away the blood of workers” (Sharif, “Little India Riots”), Singapore is, in the comical words of Ayu Candi Sari, “the country where the Merlion spits out its pee from its mouth (“My Life is Like Bonsai”). It becomes a place that is both strange and tender, where life is simultaneously “like walking on egg shells” and “like an ‘Ice Kachang’: sweet and colourful, cold but heart-warming” (Lina Porras, “My Life, My Experiences and Discoveries”). Migrant poets now rework the textures of precarity into scenes that are strangely beautiful.

Furthermore, actions border on the impossible and absurd. Perhaps the most striking instance of irrealism is in Jon Gresham’s “Man and Wheelbarrow” and Pardeep Toor’s “The Waiting”. Toor’s speaker hurtles toward a better future, pushing “the wheelbarrow of [his] thoughts” forward in an out-of-body experience, while Gresham’s narrative transforms a protest against wage theft into a comic, fairy-tale spectacle: a worker resolves to traverse the HarbourFront cable cars with a wheelbarrow on his back, smiling and “knowing the dance of a thousand bamboo scaffolds”. This absurdity resonates with Grace Chia Kraković’s “Dewy” where a host of plants sprout from her body when a sexually-assaulted domestic worker dies; Dave Chua’s “The Disappearance of Lisa Zhang” where a spirit hides the child of an abusive employer—as well as Deepak Unnikrishnan’s Temporary People, where migrant lives in the Gulf States are similarly animated by improbable events: migrant workers can fall from heights and be glued back together, grow on trees, or transform into a suitcase by swallowing it.

As mentioned, the alienation and struggle faced by the migrant precariat lends itself easily to irrealist forms of representation. When everyday life is marked by displacement and precarity, realism can no longer fully capture their lived experience. Instead, the surreal, the spectral, and the dreamlike become more fitting modes through which to express the contradictions of migrant life, of being fully alive yet reduced to disposable units of labour. Interestingly, in the irrealist visions of C&R2, migrant poets subvert expectations of horror and the eerie, opting for more playful articulations of the surreal.

Finally, C&R2 consists of dreams of more equitable, leisurely lives in Singapore. Ellen Lavilla and Eddie Tay imagine a domestic worker hosting friends for lunch at her employer’s home, while Jo Ann A. Dumlao’s “Nuri in Her Wonderland” playfully stages a domestic worker borrowing her employer’s dress for a photoshoot. These imagined freedoms, set against real-world consequences such as the Parti Liyani case, become brave acts of daydreaming. They are small but powerful assertions of autonomy, and assertions that migrant workers, too, should be allowed to desire and dream.

Professional dreamers: Shy, Rolinda, and Omar

During this period, migrant writers also began sharing more of their work independently of local publishing circuits, self-publishing their collections and posting their writings on social media. Female writers also became increasingly active in the migrant poetry scene. In 2017, MWPC saw its first women sweep, with the top three prizes going to Deni Apriyani, Naive Gascon, and Fitri Diyah. In 2018, female writers were also featured in the collection of migrant domestic workers stories published by HOME, titled Our Homes, Our Stories, as well as Familiar Strangers, an anthology of poems and short stories by Indonesian migrant workers. Around the same time, Migrant Writers of Singapore was formed by Zakir and a small group of other writers, supported by Sing Lit Station. Sing Lit Station offered a venue for their programs, also helped to programme workshops with writers who were willing to facilitate for free. The group became extremely active during Covid-19; female workers (including Mary Grace, Janelyn Dupingay, and Elli Ody Munson) were core to MWS’s activities during Covid, forming and moderating a Facebook group called “Daily life in Covid-19”.

Out of the three individual collections published during this period, two were written in English, by female domestic workers from the Philippines: Rolinda Onates Española’s No Cinderella? (2020) and Shy Lhen Esposo’s Dreams are my Reality (2019). The third collection, Migrant Life (2019) was written in Bengali by Omar Faruque Shipon, a Bangladeshi shipyard worker, and translated by an independent writer and translator based in Dhaka, named Zubayer Ahmed. These collections mark a different publishing dynamic from earlier collections that were largely written and published with the support of the local literati. Rolinda’s collection had been turned down by major Singapore publishers (Whitehead, “My”), taken up instead by Word Image Pte Ltd, a smaller, independent publisher here. Shy’s and Omar’s works were published outside of Singapore: Omar published his work with Care Printers in Bangladesh, while Shy self-funded her own work, publishing them through a printer in the Philippines who specialises in novice writers and poets (Zhang, Modes 250).

Writing in these collections is a form of dreamwork. In the self-introduction to her collection, Shy calls herself a “professional dreamer”; Omar also calls himself a “reverist” in the subtitle of his book. These poets write a fully-fleshed migrant subject into existence, one that has desires and dreams independent of their labour. If the MWPC era works lived in the shadow of the Riot’s unruly mob, seeking to humanise the migrant worker as moral subjects who toils for their loved ones back home, these writers refuse to conform to the same moral pressures to perform industriousness and selflessness in their verses. The expectations placed on migrant workers find their clearest expression in the laudatory praise accorded to the “migrant heroes” of the Tanjong Pagar sinkhole and River Valley shophouse fire. Yet, these writers no longer seem to strive towards the ideal of a good migrant, one that labours above and beyond expectations to selflessly ensure the wellbeing of those (usually locals) in their second home.

For them, writing is not merely an escape or confession, but a form of pleasure that sustains them through alienation and silence of a precarious life. Their words are frank and irreverent, refusing to sanitise the complexities of migrant life, and instead transgressing boundaries ascribed to the migrant precariat. In contrast to the silence that surrounds the migrant subject in earlier poems, the characters that these writers dream up converse with those around them.

In Dreams Are My Reality, Shy’s stories and poems eschew the drudgery of domestic work, instead evoking people and themes that she holds dear. Written in English, her stories and poems range across romantic and melancholic registers: relationships end in happy marriage proposals in “Recalling my Dreams” and “Cyber Love Affair”, a family back home dies overnight after a last Skype call in “The Sixty Minutes”, and transient migrant romances kindle and die out in “I was born to make mistake” and “Sorrowful Dream”. Told in a stream-of-consciousness style, through sentences that seem to carry on into the next, often without fullstops, these works blur the line between dreaming and waking, fiction and reality.

Women’s writing in this corpus, as Whitehead observes in the foreword to Rolinda’s collection, tends to adopt a folksy, democratic style (5). Both Shy and Rolinda write primarily in the first person, addressing a “you” that might be a Singaporean reader, a child back home, a lover, or even God. Writing in English, their second language, they do not always adhere to standard grammar, producing unexpected turns of phrase and rhymes. Their poems refuse pretence, speaking in the cadences of everyday life. As Whitehead notes, their writing does not get “prettified and refined out of authenticity and recognition” (3). Instead, it reflects a form of linguistic and emotional honesty that anchors their dreamwork.

For Shy, writing is a way of surviving the heartbreaks and betrayal she faces while working abroad. This is most clearly articulated in the poem “Shy”. The speaker describes the hurt of being lied to by someone in snatched, brief lines that span a handful of words at a time, a contrast to the more rolling nature of her other poems. A double waking is staged within the poem, first in the realisation of betrayal, then a release from the grip of despair. The poem ends with the speaker telling herself:

Wake up! Open your eyes

Smile beyond your Sorrow and aches!

You are not alone, SHY! you are NOT.

The poem gestures towards a future where the migrant worker has managed to leave his present precarity firmly in the past, building his life in a place where he thoroughly belongs. Yet, without any details marking it as a place in either nation, it exists in a timeless elsewhere that is neither Singapore nor Bangladesh. The poem ends with an extension of utopian generosity:

If your city has no shade from the sun,

come to my city,

let it be your shelter

stretching thousand new branch.

The imperative she gives herself shows how poetry becomes a practice of self-consolation; through writing, she creates a space where she can confront her sorrows and emerge with renewed strength.

In contrast, Rolinda’s No Cinderella? uses humour and rhyme to confront the absurdities of life as a domestic work in Singapore in a playful manner. Choosing to write in English, her voice is unapologetic and confident. Her poems are often irreverent, directly challenging ex-employers and Singaporeans who look down on migrant workers. In “High Enough”, she refuses to be erased, rejecting the role of a spectral, alienated figure that previous poets felt consigned to. If she is made a “wandering ghost” by those who ignore her greetings, she is a sarcastic, taunting one who asks if their rudeness is because “hello (is) a foreign word to [them]?” In the poem “Migrants are We”, she likewise proclaims that she writes so that “people will see [them] real”, refusing to be invisibilised. The poem delights in wordplay, pairing “smelly” and “flowery” in mischievous rhyme to show how migrant workers shake off derision and condescension through the act of writing.

Rolinda also exposes and ridicules the ways in which domestic workers’ bodies are policed. In “ABC of Ministry", she adopts the abecedarian form to parody the bureaucratic language of state directives that require employers to send domestic workers for their mandatory 6-monthly medical examination. As the Association of Women for Action and Research (AWARE) highlights, such exams, which test for pregnancy and sexually-transmitted illnesses, create a “culture of fear” (89) and strip female workers of basic bodily autonomy and dignity. Rolinda’s satire cuts sharply through this dehumanising logic, mocking the state’s obsession with whether a domestic helper “was / screwed or not,” and the absurdity of a regime where “sex is not allowed for them.”

Refusing such expectations, Rolinda uses her writing to cast the migrant woman as a figure not of virginity or virtue, but of ungovernable vitality. In “Love Lust,” she lays out the very human facets of jealousy and desire. She curses out her lover through striking pairs of similes:

I am your vitamins, you are my lethal injection

I am your cure, you are my incurable cancer

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I am shoes to your stinky feet

A deodorant to your sour sweat

A toothpaste to your bad breath

A tissue to your shit

Despite the repulsive features of her partner, she reveals her devotion to him: she wears “clothes so revealing” to ward other “bitches” away. Rolinda is unsparing and self-aware, turning love’s abasement into biting comedy. In “Appearance”, too, she revels in tattoos, shorts, and piercings, an aesthetic that is at odds with the demure, desexualised role often expected of a domestic worker. Domestic workers are sometimes “perceived as a threat to the family unit” (HOME), under suspicion of seducing the men around them. Through Rolinda’s writing, a migrant subject emerges who is unapologetic and defiant, refusing to conform to the expectations foisted onto domestic workers.

Likewise, in Omar Faruque Shipon’s Migrant Life (2020) , the migrant subject is allowed to have obsessions and desires, even if they might appear unsanctioned or immoral. He is tempted to take what does not belong to him in “The Blue Punjabi Suit”, developing a surreal obsession for this piece of clothing. He lusts over a girl he meets on Facebook in “Identity”; and in “My Happiness”, he indulges in vices like drinking and smoking while staring lewdley at the beer waitress’s breasts, before launching into a recount of the sacrifices and pressures he faces with his family. Additionally, his encounters with those who have attained permanence in Singapore assume a surreal, dreamlike quality in “Limitless Love” and “Love of Farhan”. The Bangladeshi men he meets through these fleeting conversations, who have second wives or foreign wives in Singapore, seem almost like projections of his own desires, existing somewhere between reality and fantasy, and highlighting the impossibilities of permanence for a migrant worker.

Beyond these transgressive but powerful desires, Omar’s writing also offers up a sense of community, capturing the everyday solidarities that sustain migrant workers in the dormitory and worksite. In “Elusive Dream,” a fellow Bangladeshi worker is suddenly repatriated. Omar writes, “I know how horrible the pain is of broken dreams”, framing it as a shared fracture in the collective migrant imagination. “Death of a Mother” tenderly depicts a lie told out of compassion, when the speaker hides the news of a friend’s mother’s passing. He depicts these colleagues with affection and tenderness, mourning for the death of a Myanmar colleague in “Paing’s Death”, and rooting for Kabil in “Strain and Struggle”, who is thin “like a pencil” and whose elopement with his beloved seems “like a Tamil movie”. His stories unfold a world of precarious community: “Room Leader” stages the dormitory as a democratic microcosm, where conflicts over noise, snoring, and space are resolved through consensus rather than authority. Across his poems and stories, the migrant subject refuses to be isolated and alienated. Such cross-ethnic portrayals articulate what one might call a poetics of solidarity, a dreaming beyond borders, toward a transnational fraternity of the migrant precariat in Singapore.

Poets as advocates: Zakir and Sharif

Migrant poetry in the period leading up to and during Covid-19 also assumed a much more political charge. Two poets in particular emerged as poet advocates, eventually becoming a part of Singapore’s civil society scene: Md Sharif Uddin and Zakir Hossain Khokan. Their poems develop a much more pointed, political edge surrounding the systemic vulnerabilities of the migrant precariat. Through verses that oscillate between clear-eyed critique and manic laughter, they trouble Singapore’s capitalist realism and dream towards a better future.

Sharif’s voice came to be seen as representative of migrant workers’ in Singapore; following his earlier commission for Gwee’s Written Country, he was also invited to contribute to others such as the Tan Chin Tuan Foundation’s Inside (Out). His earlier book Stranger to Myself (2018), which won the Singapore Book Award in its year of publication, had already stripped away the city’s sheen to reveal the systemic vulnerabilities that migrant workers faces in Singapore. As Gwee notes in his review of the book, the “migrant worker’s life is unnatural. It comes to exist by means of fundamental violence”. From the lack of enforcement of laws around wage theft and illegal overtime work to stunningly low salaries, poor food and unsafe transport, Sharif writes about the realities beneath the migrant dream. The critique within his writing is, as Gwee points out, encapsulated within the “recurring image of the volcano”; likewise, Whitehead comments that “it seems a wonder he and other workers aren’t screaming, protesting their rights” (in Asiatic 221).

In other words, unlike earlier texts, Sharif’s works do not merely ask readers to feel for the suffering worker and treat them with more respect. Compassion becomes insufficient, and his critique invokes a response that is more systemic than superficial. In dreaming and writing, he makes a different world imaginable. Interestingly, Sharif’s voice becomes fragmented between systemic critique and declarations of hope and love for this city of dreams, as he advocates for the migrant precariat in a capitalist realist state that insists there is no alternative.

His writings during Covid-19, composed in English and published in his second collection, Stranger to My World (2021), continues this line of pointed critique. In “Day 2”, he writes:

I know that the role of migrant workers in building this dream city is immense. So the government must consider our problems.

In Sharif’s (and, as will be seen later, Zakir’s) writings, the migrant poet speaks to and about the Singaporean government. This direct address marks a shift in migrant poetry, at times veering into angry and bitter registers, presenting calls for change on the level of policy. Sharif’s political addresses also touch on a handful of topics that form the focus of migrant activism in Singapore; these include the lorry problem (in poems “Return to Company Dormitories" and “Work After a Long Break”), dormitory conditions (“Crazy Delirium”) and catered food (“Food for Thought”).

Despite these critiques, the migrant poet simultaneously praises Singapore. While critics like Zhang suggest that this is performed out of fear of state censorship, there is also a sense of genuine pride and affection for this second home that emerges in his writing. While criticising the Singaporean government, Sharif also urges his fellow workers to be cautious in how they represent Singapore to the international press: “We want to present this city as a dream city to the world. This is our second homeland” (Day 6). Fellow workers, too, display sincere admiration for state leaders; as Sharif writes, “Mr Lee is now very popular among migrant workers. Many have already added his photo to their profiles” (Day 17). This coexistence of reverence and reproach, where critique emerges alongside the language of devotion, reflects the schizophrenic condition produced by Singapore’s dreamwork.

The dreamwork of Singapore, if you recall, is to forget the cracks and contradictions of its neoliberal regime. Despite the violence and precarity that is built into its policies around cheap migrant labour, state agencies and mainstream media paint rosy pictures of migrant well-being through periodic Employment Standards Reports and satisfaction surveys that portray Singapore as a benevolent host. With Covid-19, this is perhaps best encapsulated in then-Minister of Manpower Josephine Teo’s tone-deaf response to Nominated MP Anthea Ong’s question about whether the government would apologise to migrant workers for their living conditions: “I have not come across one single migrant worker himself that has demanded an apology”.

Dissenting voices are frequently dismissed by ministers as a vocal minority, especially in the era of social media (Wong, Lee in Teo X), and policed through the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act 2019 (POFMA). As activists and academics like Kristen Han and Cherian George point out, POFMA gives the state impunity to silence dissenting voices in the name of protecting public confidence in government institutions. It becomes a mechanism through which the state discredits activists as troublemakers with an agenda who threaten the social fabric and peace of the nationstate. The erasure and censorship of voices which contradict state narratives produces schizophrenic political subjects. Activists who do the work of witnessing and articulating the contradictions behind Singapore’s dreamwork are denied by the state which insists on a rigid version of reality. As a result, they have to constantly straddle the ethical compulsion to expose the violence and exclusions of the city, and the risks of doing so.

The strain this places on Sharif borders on madness and paranoia, exacerbated by the conditions of Covid-19. As work resumes after the first circuit breaker, Sharif recounts the strain of having “to put on a bright ‘I love Horlicks’ smile to say that all is good” (“Supply Man”). The strange interjection of this packet drink, carrying echoes of consumer advertisements, seems to gesture towards Sharif’s powerlessness in the face of the unfeeling march of capitalism. When he suffers from piles, he describes the indignity of struggling to get transport to the clinic in “Breaking the Rules”, having to take a cab when it was deemed criminal behaviour because of Covid-19 regulations. Yet, he has to “talk to everyone with a smile”, silently shouldering these indignities (“Community care facility (I)”).

The crazed pressure of maintaining a smiling facade elsewhere explodes in manic, illogical laughter. When he sees a picture that someone else had posted of a crowded dormitory, of 35 pairs of sandals outside a room, Sharif is not saddened or angry. Instead, he “thought that it was funny because what could be more interesting than so many migrant workers crowded in a room like a herd of cattle?” (“Crazy delirium”). The immense stress of being the only breadwinner for a family back home, laden with debt, is recast in similarly manic terms in the poem “Migrant Life”. The rhythm of labour is unceasing:

I am busy in the morning

I am busy in the afternoon

I am busy at night.

Swept up in this crazed rhythm, the speaker loses sight of the love and desire that previously motivated the migrant poet. Instead, he “want[s] to inhale the perfume of money”, and “Laughter explodes in [his] head.”

Dreaming of a better life, and advocating for his fellow workers, can feel like a crazed endeavour in Singapore. The psychic strain of dreaming and advocating in the time of Covid-19 filters through Sharif’s writing in cursed eyes, and malicious ghosts. The migrant precariat does not just haunt the Singapore cityscape, but becomes haunted by his own shadow. During lockdown, Sharif looks at the city “through dead-fish eyes” (“Under House Arrest in the Dream City”); in a dream, he looks into the mirror to find his “Father staring at [him] impassively in the mirror” with “one red eye” (“Day 21 (I)”). The eyes with which the migrant poet-as-activist looks at the world is seemingly cursed, diseased and itchy. Ghostly presences lurk around him too, opening the toilet door to peer at him and touching his feet in his sleep (“Ghost”). These surreal episodes evoke the psychic toll of captivity and activism. Yet, Sharif dreams on, resurrecting “fossil dreams” (“Taken From Life”) and insisting, “I will dream again / I will dream again” (“Happiness”).

Similarly, Zakir became a key organiser and advocate for migrant writers. Supported by local bookstores and cafes such as Booktique, Books Actually, City Book Room, and Artistry, Zakir continued to organise literary activities. Together with a few other migrant writers, he started the Migrant Writers of Singapore group in this period. His “One Bag, One Book” initiative also aimed to make books more accessible to workers, so that every worker can read at least one book a year (Khokan 48). Starting from 2017, the Amrakhajona book fairs were revived as Singapore Bengla Literature (SBL), and “Poetry Evening With Migrant Tales” sessions were held (Khokan 48). He also took on editorial and translation roles for a number of local and international collections including the Call and Response anthologies, Translating Migration: Multilingual Poems Of Movement, and To Let the Light In by the Asian Pacific Hospice Palliative Care Network.

Like Sharif, Zakir turns his poetry into advocacy, but adopts a more angry and acerbic tone. By self-publishing primarily on Facebook, and occasionally contributing to websites based outside Singapore, he and other migrant writers around the time gained a huge amount of autonomy over how their experiences are represented. On Facebook, Zakir emerged as a community leader of sorts, and a number of fellow Bangladeshi workers followed his profile. He thus wrote primarily in Bengali, but would occasionally publish poems in English on Facebook for his Anglophone followers (consisting of other local and migrant writers). Two poems in particular are worth exploring here for their political significance: “First Draft” (2020) and “Please Do Not Call Us Your Brothers” (2021). The first was written in Bengali, while the second was written and published in English.

“First Draft” was translated by Debabrota Basu and published on Southeast Asia Globe, a regional news website. It begins with repetition and fear (“They are afraid / Afraid”), the phrase becoming a chorus that mocks the absurdity of social distancing in dormitories so crowded that workers could only “measure wrinkles on their foreheads”. Zakir’s sarcasm and anger threads the poem, describing the ways in which workers cannot eat, sleep, or laugh in these conditions, becoming heavily censored:

They are afraid to read.

They are afraid to write.

They are afraid to draw.

They are afraid to take photos.

They are afraid to make films.

They are afraid to learn, to gaze.

They are even afraid of appreciation for their success.

Ssshhhh, they stay silent!

In the face of this muteness, Zakir’s writing is a powerful act of defiance. The poem ends with bitter sarcasm, as he suggests that their official documents, stamped with the label “Modern-day slaves”, have at least “saved them from an Identity Crisis.” The closing line carries echoes of Sharif’s manic laughter, and the declaration: “They will laugh. They will laugh out loud” is a haunting refusal to succumb to despair.

In “Please Do Not Call Us Your Brothers,” Zakir’s tone is likewise openly accusatory. It begins with barely-concealed anger, despite its politeness:

Minister of Manpower Tan See Leng

Please do not call us “your brothers”

While others like Sharif and Omar have previously addressed specific ministers like Louis Ng in their publications, often with respectful acknowledgements of his efforts to speak for migrant workers and other marginalised groups, Zakir’s work is a bold anomaly. It is one of the only instances where a migrant poet directly calls out a Singaporean minister in critical, even confrontational terms, breaking from the polite gratitude that ministers like Josephine Teo are used to hearing from workers.

The poem is interrogative and sharply questioning, demanding explanations for the mistreatment of migrant workers during the pandemic. Significantly, the speaker signs off on the behalf of “Workers from Westlite Dormitory / Jalan Tukang, Singapore”. While Zakir did not reside in Jalan Tukang at the time, he signals a fraternity with the migrant workers living there while disavowing the state’s empty or tokenistic attempts to connect with its migrant precariat over a similar brotherhood. The poem reads as both accusation and protest, its fury tempered by lucid lines of questioning.

Through these poems, Zakir and Sharif dream boldly of a future where the migrant precariat is treated with fairness and dignity, making it imaginable through their writings.