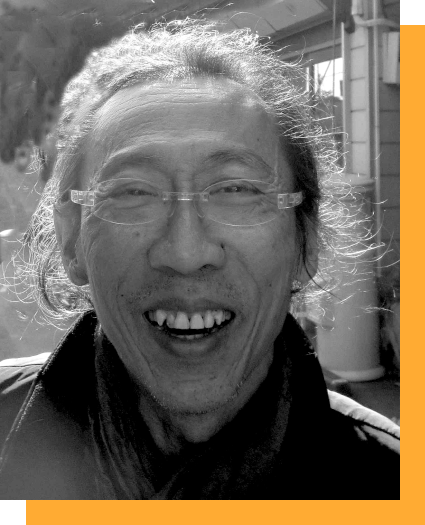

Lee Wen (1957–2019)

CRITICAL INTRODUCTION

“I bite because I was alive and hungry”: The Punk Poetics of Lee Wen

Written by Ra Ebrahim

Dated 25 Jul 2025

Lee Wen’s practice, of both poetry and performance art, has always been informed by the visceral vocabulary of embodiment. His meditation on otherwise abstract concepts, such as the rigid bureaucratisation of race embodied in the hyperbolic Yellow Man series (1992-2012), gestures to his artwork as a poetic refraction of these concepts as they pass through and out of the body. Lee’s language of embodiment was, therefore, not only confined to the words he produced, but spanned throughout his entire oeuvre. Though some of what eventually reaches us as readers of his work has been coloured by his difficult experience of Parkinson’s disease, given that his body could no longer function the way it once did, Lee refused to despair.

Elaine Scarry once wrote that “Physical pain is […] language-destroying,” (The Body in Pain, “Introduction”, 19). This mirrors a sentiment previously expressed by Virginia Woolf, who laments that the same English language that at its lofty heights produced Shakespeare still “has no words for the shiver and the headache” (On Being Ill, 34). While these lines have cemented themselves in the lexicon of literature about bodily pain, the written works of Lee Wen show that they do not have to hold true. Instead, he “learned from pain and noise that there is still so much to do” (Boring Donkey Songs, Lee Wen 123). The relentlessness of his writing practice, much like that of his performance art work, insisted that pain could not obliterate his instinct towards expression. He wrote prolifically, beginning with A Waking Dream in 1981, a collection of drawings and poetry which foregrounded his interest in perceiving the gap between life and reality as it is experienced. This interest lasted throughout his career and his publishing collaborations with Greys Projects, including the conversational We Here Spend Time in 2013 and a collection of candid poems titled Boring Donkey Songs, which was published at Singapore Art Week in 2017.

Lee Wen was born in 1957 in Singapore, Malaya, and the rest of his life would unfold just as enigmatically as it began. As a student at Raffles Institution, he loved books and the arts, although they were not perceived as viable pursuits at the time (Lee Wen: A Life in 135 Parts, “Reading as Shameful”, Chan 60). It was only after having his tentative manifesto, 1981’s A Waking Dream, published by William Lim’s Select Books, that he eventually quit his job at a bank and enrolled in at the then Lasalle-SIA College of the Arts, now LASALLE College of the Arts, in 1988, aged 30. It was here that he met the artist Tang Da Wu, with whom he formed The Artists’ Village (TAV) after graduating from Lasalle in 1990. A mere two years later, he first performed Journey of a Yellow Man (1992), his most enduring series, which built on the experience of feeling hyper-racialised. Another two years later, the government imposed its ten-year funding ban on performance art following Josef Ng’s Brother Cane (1994) The year after this ban was lifted, in 2005, Lee Wen was awarded the Cultural Medallion. His practice thereafter was spread far and wide. From the challenges he dealt out in his performance art, to his work eventually being lauded by the institution in his being awarded the Cultural Medallion, it seemed there was no place Lee’s work could not go.

Lee’s wide-ranging and playful writing practice embodies what I describe as a “punk poetics”, a form that refuses the divisive properties of categorisation, and instead insists on persistence, play, and community. While Lee himself would likely express some distaste at being boxed into any category at all, even when that category occupies a space of resistance, this formal quality is not without reason. Lee identifies “as punk as they come / and go” in “untitled” from July 2014 (Boring Donkey Songs, 89), and also actively participated in the local punk scene, which was captured on film in SCENE UnSEEN by the late Abdul Nizam and friends. Additionally, a crucial element of punk is its sense of playfulness, which manifests in collective activities like that of moshing, which brings many bodies together in a shared action. Lee’s punk sensibility enfolds in itself a willingness to be playful. In his work, this is synonymous with a forthwith tendency to issue challenges against what he believed were divisive establishments. This is embodied constantly, as when Lee makes reference to a collective via the possessive “our” or the pronoun “we”, he is referring to “humanity at large” (We Here Spend Time, 2013, 19). At the same time, Lee’s willingness to be playful also manifests as a movement across different forms and aesthetic categories, with a focus on creativity and expression, without limits.

Fellow poet and artist Jason Wee notes as much in his introduction to Boring Donkey Songs when he writes about the “collaborations-contaminations” (2) that saturate Lee’s writing in the collection, and the “perversity” of the work that refuses to adhere to a single form or register. This indiscriminate mixing of supposed high and low culture, through references to seminal moments in Singaporean art history coupled with many a crude reference to expelling gas, foregrounds the carefree attitude Lee had when it came to categories and the divisions that they enable. Or, as the speaker declares put it, in “untitled” from March 2013:

but there is the Institute of Sick Artists

who think they are very smart

and try even to pretend they know art

when they only now and then breath and fart.(15)

Freedom has always been a primary concern for Lee Wen, even and perhaps especially in his performance work. The immediacy and ephemerality of his performance work allowed for explorations that might not have been possible if they were to be nailed down or institutionalised in galleries or museums (“Remembering Lee Wen: The Anatomy of Dreamers”, Belarmino 2020). For instance, the organic encounters created by the series Is Art Necessary? What Is Art Good For? in the late 90s and early 2000s emerged because they took place outside the sanctified atmosphere of a gallery. In a piece of video documentation, Lee walks around Singapore’s marina with his arms outstretched in the universal gesture of invitation, holding aloft two blank boards to collect the insights of his participants. Once again, Lee uses the work of his body to break down any perceived barriers, and aligns himself in pursuit of connection with others.

In a similar vein, the wide-ranging forms of his writing demonstrate a deep hospitality, which might at first appear puzzling but is never cold nor aloof, as it always eventually reveals itself to be intensely generous and welcoming. When the speaker declares, “my songs are not just music / nor mere words / they are prayers:-” in “untitled” from May 2014 (71), these short, sharp songs feel strangely familiar for their simple, everyday language and consistently embodiment of a turn towards an all-encompassing community. While poetry is often considered a lofty or impenetrable form, Lee’s writing refuses these barriers in favour of unity. Much like the quickfire music of punk which keeps the concept of its community front and centre, Lee’s writing returns to the same concern; that is, always for the other person, the other people in the community, and the myriad forms of collective action and care that could result. While one could label this an anti-establishment attitude, which Lee certainly had, his concerns were not just against the “uncompromis[ing]” state-sanctioned pragmatism and coldness (14). Rather, his sentiments formed their own orientation by becoming aligned in movement and collective action, in the kind of violent playfulness one might witness at a punk gig, where the audience pushes their bodies together to create their own vocabulary of movement. A similar sensibility towards collective action is what creates the unassimilable quality of his work, as his interest in dreams across his oeuvre “is his reminder that our dreams, even daydreams, remain unassailable and unassimilable by the forces of the powerful”. (The Artist Speaks: Lee Wen, “Introduction: Lee Wen”, Tan 13) Playfulness is unpredictable. It is born out of an imaginative capacity that cannot be held down by pragmatic concerns, and it is this which allows Lee’s work to keep its candid qualities, while remaining elusive.

From the outset, Lee’s writing displays a disdain for the limiting properties of category, and the guise of inherency that it claims. In particular, his punk sensibilities exercise this suspicion in response to state-sanctioned political categorisation, with him noting – for instance – “how left became a dirty word” in “untitled” from February 2013 (Boring Donkey Songs, 14). The possibility for transfiguration in the word “became” suggests that there is no inherent quality to the left. Instead, as the speaker goes on to elaborate in the same poem, “The PAP, in its present form, is a right-wing party. […] Being right-wing means being uncompromisingly unapologetically pro-business to the very end”. As a result, the transfiguration of the word “left” into something “dirty”, when set in proximity to his claim of the PAP’s right-wing status, has two sets of implications. The first, is that a wider set of political narratives are at play, the same tendencies which brought about the anti-communist covert Operations Coldstore and Spectrum. The second, that it is these political narratives that subsequently construct meaning in wider political and social life, thus allowing for “left [to become] a dirty word”.

This disregard for category extends beyond worldly matters and into the nebulous realm of identity as well, where he slyly remarks, “dead am i but only so i still am me” (84) in “untitled” from July 2014. In this, he troubles the connotations of categories such as “dead” and its subtextual opposite “alive”, as well as the very notion of “i” or “me”. The tenuous connections between each of these qualities surface in his writing before being playfully meshed to create an entirely new schema. Even life and death evade existing structures of understanding and knowledge, as he places the effacing state of death with the life-affirming “i still am me” Even popular figurations such as “Punk is dead” fly through his fingers and emerge in the balance of “punk not dead its just not alive” (157), continuing to refuse simplistic dichotomies, such as that of life and death. For him, legibility is a reductive state. Lee goes so far as to apply this to his own identification as punk, as his speaker breezily declares himself “punk as they come / and go” (89), where the first line embodies an intensity of being “punk” only to immediately be offset by the fleeting staccato of “and go”, showing an awareness that too much attention to category is antithetical to the (comm)unity he’s interested in.

Having cast aside category, play emerges as the dominant form of Lee’s work, constantly happening around and between category as an unrestricted and unself-conscious movement. Given that play emerges from one’s own imaginative capacity, the only thing play is bound by is the mind and its own submission to the external structures that attempt to govern being. As a result, Lee’s punk poetics are of a necessarily playful genre that forms its own kind of resistance against dominant or overarching narratives, in which he takes aim at the censorship typically observed in bureaucratic contexts. Due to its own affinity for categories and rigidity, bureaucracy is unable to categorise or censor play, as satirised in the smothering image of “curators armed with fire extinguishers” (59) in “untitled” from March 2014. Recognising how even the institution of the museum is intertwined with the state apparatus of censorship, these so-called guardians from the state can only aim fearfully and indiscriminately at art, smothering it out of fear. Against this enveloping impulse, the slipperiness of play then makes it all the more worth pursuing as a form of resistance and of articulation, as its imaginative capacity so far exceeds the narrow and myopic scope of bureaucracy and its practices.

In its playful punk way, Lee’s writing moves through and between modes of understanding without submitting to being pinned down as the work of certain type of artist or writer. Though this can be frustrating, as is explored in his remarks on the critics and institutions who only talk around “the gist” of what he does (104), this inability to totally clarify or make his work entirely legible is what maintains the dignity and force of its expression. Although many of his poems and written works make the turn towards a community or a call for collective action in a way that some might find predictable, the form of this turn – which is always playful –continues to surprise and disarm. For instance, in his writing about a past that weighs heavy and drags down the imaginative leap necessary for the future, Lee ends “untitled” from July 2014 with a strangely optimistic and lovable call to community:

…we all gonna live not let that bonb eco hydero atom edge of the edges

No siree unless we let it doom us like the empty darkest nightmares

say no but Y E S it is possible foe and friends roll together and bake that

a long roti

a breakfast for the planetary revolution…

Though he begins with the sombre mention of nuclear apocalypse and the masses made to live at the “hydero atom edge”, always anticipating the worst, this dire acknowledgement lives directly alongside the unapologetically whimsical image of communal baking littered with an imperfect field of spelling errors. This image of people lined up as far as the eye can see, rolling together “a long roti” as “a breakfast for the planetary revolution” is the manifestation of an unpolished communal effort to come together, in the corporeal activity of nourishing oneself and each other always in pursuit of better conditions.

Similarly, the unconventional linguistic formations of “[n]o siree” and “Y E S” are manifestations of his tendency to adopt somewhat nonsensical formations, abandoning antiquated traditions such as the iambic pentameter or rhyming couplets for the more digitally-informed free verse, often incorporating repetition or the familiar short-forms of text-speak. A reader might initially find themselves trying to analyse his work, but these formations so defy logic that one ends up having to follow him down his sunflower-laden path (50), heart-first. The poems therefore become an affective experience more than an intellectual one, which is not to say that they are devoid of intelligence, but that the approach that they encourage is one that is fundamentally human and heartfelt.

It is in moments like these where Lee’s primary concern shines through; his turn is always moving out of himself, and towards others. This is evident not just in his own writing in Boring Donkey Songs, but in the recollections of the people who knew him best. Poet Jason Wee, for example, writes about the first time he saw Lee Wen in “The Last Flash Back And Forward And Back And” in his collection An Epic of Durable Departures. The speaker describes Lee

knock[ing] a few back

red as plastic cups

at a gallery opening,

you insulting your friends

with a sound

halfway between a ruthless

trouble and defeat…

Despite the moment of antagonism captured in this fragment, the vitality of this encounter is so vividly described that it’s clearly a product of a deep affection for this courageous personality, who had enough integrity to be “ruthless” to his own friends. The vivacity of this moment, elaborated upon in the colour of the cups and the viscera of the “sound” the speaker describes, brings to life the personality of his encounter with Lee. Though the speaker is only an observer, the animation of the moment stands in stark contrast to the faceless collective of bureaucracy that saturates Lee’s other poems and informs his qualms about participating in the world of contemporary art.

Ultimately, these concerns cumulate in “prayers” (Boring Donkey Songs, 71), each only a few lines long, and often filled with simple and welcoming diction which makes the potential for his audience wide-ranging and generous. I see this as an underlying principle of his punk poetics, in that if his work truly is to benefit and include everyone, this inclusion is also something that must performed on the level of form. Just as there are many punk songs that burst into the world screaming at two minutes or less, Lee’s poems cut the page, short, sharp, and clear-voiced. Though poetry is often vulnerable to being dismissed as a pretentious or inaccessible form, the truth is, Lee’s poems are considerate of every one, as they refuse any sort of pretension, and insist on including familiar cultural incorporations – such as the aforementioned “long roti” for the revolution – effectively remaining local while illustrating a matter of universal concern.

Across his body of work, Lee Wen never held himself aloft as an artist. Instead, from his early work like 1981’s A Waking Dream all the way to Boring Donkey Songs, he consistently emphasised that

…art is only a dream

for us to carry yonder in reality

it must be

with commitment in solidarity(213)

This viewpoint, stated so plainly, is the most crystallised formation of his thesis as an artist, in that art might be a manifestation of a subconscious desire, but the real work will always come in what we can do with and for one another. These poems are a testament to that full ‘commitment in solidarity’ that Lee imagined, as they embody the principles of consideration and the importance of community at every single level, both in form and in content. In doing so, they dart around playfully, zipping up and down our consciousness, refusing to be pinned down as a legible singularity. Instead, the written work of Lee Wen is an empathetic set of prayers that is always oriented towards a boundless community, while never fearing to rear its head to “bite because [it] was alive and hungry” (112).

Works cited

Belarmino, Vanini. “Remembering Lee Wen: The Anatomy of Dreamers.” National Gallery Singapore, 5 March 2020. <https://www.nationalgallery.sg/sg/en/learn-about-art/magazine/remembering-lee-wen-the-anatomy-of-dreamers.html>

Chan, Li Shan. Searching for Lee Wen: A Life in 135 Parts. Singapore: Epigram Books, 2022.

Lee Wen and Jason Wee. We Here Spend Time. Japan and Singapore: C.A.J and Grey Projects, 2013.

Lee Wen. Boring Donkey Songs. Ed. Jason Wee. Singapore: Grey Projects, 2017.

Lee, Wen. Is Art Necessary? What Is Art Good For? (Part 2). Performance. Singapore, 2002.

Scarry, Elaine. The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Tan, Adele. The Artist Speaks: Lee Wen. Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2020.

Wee, Jason. An Epic of Durable Departures. Singapore: Math Paper Press, 2018.

Woolf, Virginia. On Being Ill. New York: Columbia University Press, 2024.